Summary

- Hellblazer #27, "Hold Me," explores social injustice and the human condition by way of the horror genre, capturing the essence of a cold and broken world.

- Neil Gaiman and Dave McKean bring their expertise to the issue, creating a visually stunning and morally heavy story.

- John Constantine serves as a flawed hero, showcasing his decency and his struggle to find hope in a society plagued by darkness.

Initially released in March 1990, Hellblazer #27 hit the shelves at a time of instability in the United Kingdom. Margaret Thatcher’s controversial time as prime minister was coming to an end amidst economic recession and rising nationalist sentiment courtesy of the far-right National Front. The boom of the eighties had buckled under massive cuts to public funding, leaving many with the sense that society’s most vulnerable had been left behind. Enter Neil Gaiman and Dave McKean with Hellblazer #27's "Hold Me," a tale of socially conscious horror that attempts to lay bare a glimmer of hope in the rising darkness.

From the front cover alone, the reader knows they are to be treated to a slice of horror. McKean’s jagged art style depicts an indistinct, shadowed creature looming over John Constantine’s face. However, it is also clear there will be more to this story than shocks and scares. Beneath the cover’s monster, Constantine’s visage is presented within a blue love heart, encapsulating the key theme of the issue, that the hearts of men are growing cold, and salvation can only be found through compassion for one another. Unlike many works of horror, "Hold Me" is worth a read because it has something deep and meaningful to say.

Gaiman’s Style and McKean’s Artwork Are Perfect for the Horror Genre

Going into "Hold Me," Gaiman and McKean were no strangers to the horror genre. The year before, Gaiman (accompanied by Mike Dringenberg, Malcolm Jones III, Robbie Busch, and Todd Klein) released the Sandman #6 story, "24 Hours." The issue is remembered as one of the most shocking ever to be published. Over the course of a day, supervillain John Dee utilizes the ruby he stole from Dream to physically and psychologically toy with the clientele of a diner before leaving them mutilated and dead. While the issue is rightfully celebrated for its shock value, what makes "Hold Me" a cut above is its weighty moralization. Gaiman presents London with a poison running through its heart. Drunken yuppies prey upon the homeless, homophobia is rampant in the wake of the AIDS pandemic, and racism runs rife. Gaiman captures the hateful, tribal zeitgeist, rendering this abstract threat as far more monstrous than any regular horror stalwart could ever hope to be.

Released in the same year as "24 Hours," McKean had recently flexed his horror chops in the beautifully crafted Batman: Arkham Asylum with Grant Morrison. From an aesthetic perspective, The Joker has never been portrayed as more terrifying. McKean brings this to the table in "Hold Me," treating readers to a near-monochrome London in autumn. Mist engulfs the dilapidated streets, and skeletal trees lurk on the edges of many of the panels. Gaiman was evidently attempting to tell a tale that captured the shortcomings of the Conservative administration of the time, and McKean’s barbed, unsettling art style was the perfect vehicle for doing so.

Constantine is the Ideal Hero for Gaiman and McKean's Tale

Since his first appearance in Swamp Thing #37 (by Alan Moore, Rick Veitch, John Totleben, Tatjana Wood, and John Constanza), John Constantine has stood as one of DC’s more problematic antiheroes. His actions are often self-serving, and he is infamous for leaving a trail of bodies (that are sometimes his own friends) in his wake. However, despite his shortcomings, the reader is always left with the feeling that a good heart lurks beneath the flawed exterior. This is one of the principal reasons that the character has remained so engaging over the decades. Despite his egregious mistakes, Constantine is at his core a man trying to do his best in a cold and broken world. Gaiman leans heavily into this to provide the moral heart of his story.

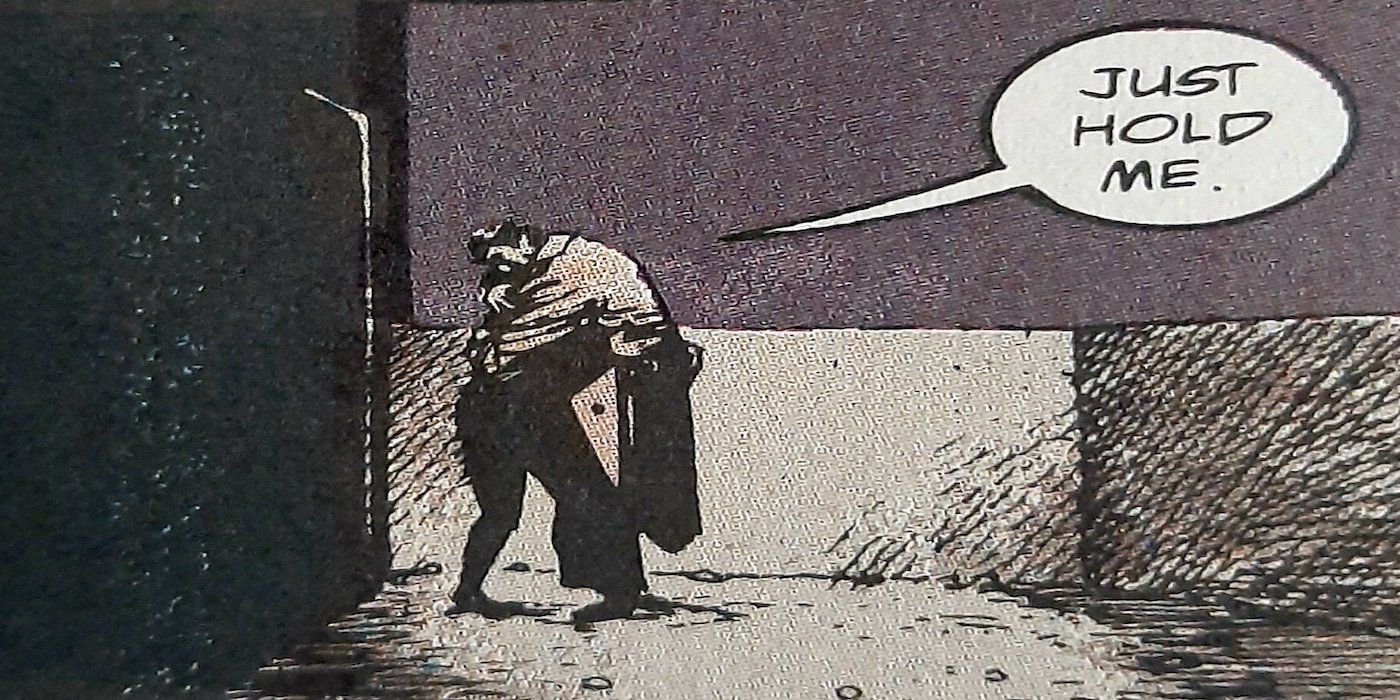

Constantine’s decency is presented early on when he leaves a taxi due to the driver’s xenophobic hate speech. However, mere pages later, he is lashing out at what he hoped to be a one-night stand. This moment provides the groundwork for Gaiman’s moral climax. After facing the tale’s “monster,” Constantine returns to the woman that he spurned, having undergone an emotional epiphany. He embraces her, realizing the comfort that people provide one another is the only thing that stands between humanity and the ever-encroaching darkness of existence. The moment is as powerful as it is bleak, perfectly capturing the essence of the character.

"Hold Me" is Socially Conscious Horror at its Best

The greatest strength and lasting appeal of this story lies in the way that it adopts the horror genre to explore social injustice and the human condition. As with all great horror creations, the power of the issue’s “monster” can be found in its simplicity. The ghost of a deceased homeless man haunts the streets of London, lumbering towards the living with a simple plea: “Hold me.” Horrified by the ghost’s appearance and stench, his victims grow cold and die at his mere touch. At a base level, the scares of the story can be found in the ghost’s appearance, with his twisted hand reaching out in fatal predation.

But Gaiman is interested in more profound, philosophical scares. The true monster of "Hold Me" isn’t the ghost at all but the apathy of those in power who allowed the dehumanizing degradation of his existence. Constantine avoids death by not recoiling at the ghost as others had done. Rather, he asks its name - a simple act of connection that humanizes the “monster.” Constantine’s choice to then hug the ghost, finally allowing him to pass on, hammers home the realization that those in power aren’t the only monsters of this tale, but rather the common man. Anyone who has ever passed by the homeless in unfounded revulsion or fear is complicit, part of a darkness far more frightening than any ghost. Gaiman condenses the moral preoccupation of the story in a singular moment. We are all humans with the same basic needs - to feel safe, recognized, and loved.

Gaiman and McKean’s "Hold Me" is that rare thing: an intelligent, socially conscious horror story with heart. Like exemplary movies of the genre, such as Night of the Living Dead (1968), The Babadook, and Get Out, the surface scares are bolstered by more abstract and deep philosophical terrors that hold a mirror to the ails of society. The story is perhaps most memorable for its conclusion. A horror mainstay since his inception, Gaiman uses Constantine as the vessel for a message draped in absurdist philosophy, granting readers a faint ray of hope in the darkness that his tale so perfectly encapsulates.

In The Myth of Sisyphus by Albert Camus, the philosopher compares human existence to the punishment of Sisyphus. In Greek mythology, the king is condemned to spend eternity rolling an immense boulder up a mountain, only for it to roll back down again every time he nears the summit. Sisyphus’s fate is futile and meaningless, but Camus concludes there is joy enough in the rolling of our own personal boulders to fill our hearts. Gaiman subverts this by locating the joy in each other. The London he portrays is dark, unfair, and cruel, and every character has their boulder, whether it is insecurity, institutional inequity, or grief. Constantine’s confrontation with the tale’s ghost makes him realize the darkness never truly fades, but when we hold each other, we feel better, if only for a minute, even if it is ultimately a lie.